Month: June 2015

Imaging study shows how humor activates kids’ brain regions

StandardPLOS ONE: Coping with Stress and Types of Burnout: Explanatory Power of Different Coping Strategies

StandardHow to Recover From Burnout at Work – The Muse

StandardUnderstanding the stress response – Harvard Health

StandardUnderstanding the stress response

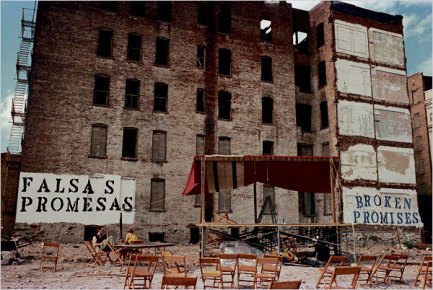

Third World Tourist by Duane Sharrock

StandardMy brush with death as a tourist, among other things, inspired me to become an educator.

I am an administrator in an alternative high school. The school is small enough that I can continue to learn and to develop with students. Meanwhile, I also connect with teachers, finding the weird, dynamic manifestations that emerged from our personalities, interests, knowledge, and skills. It’s hard to believe that my commitment and passion for self-education would blossom into a commitment for educating others and for helping kids. This commitment though was not always in me, embedded so deeply. In fact, my commitment towards helping kids began in prison.

To be accurate, I wanted to learn about how others lived. I became a residential staff member in a non secure detention center for teenaged boys as part of that journey. I supervised them.

During free-time, the boys would talk about their lives: what they did for fun, the people they knew in their neighborhoods, how they got caught and for what charges they were actually “locked up” for — which was less than what they had been caught doing (plea bargaining). Sometimes they told me things directly; other times, I overheard their discussions. We played basketball together, played cards, played manhunt, but I also supervised them and judged them, assigning chores, tagging them with restriction “days” and awarded points on their behavior charts. I developed a good ear for evasion and exaggeration, but there were also the fact explorers, inquisitors, doubters, the other kids who lived near or in the same places or even knew some of the same people, so I learned some of what kids were dealing with in their communities, schools, and homes. My confusion gave way to indignation which gave way to curiosity. I had so many questions as I learned about my cottage students in person, by observing how they spent their days under supervision and in treatment team meetings.

Why did some kids in the same family have problems with the law while the other sibling(s) did well in school or did not have arrests? What was the connection between conduct disorder and attention deficits? How did so many of these kids end up in 9th grade with terrible reading skills? Why did so many students improve in some of the structured settings while many others did not? How can we improve their lives and outcomes?

I learned mediation skills (NOT meditation) to teach students how to mediate conflicts at the high school level. In the process of negotiating and learning problem exploration, I became aware of aspects of communication I had never considered before. The trainers provided so many insights that continued to helped me to develop my own knowledge. I learned more about the power of language, beliefs, and points of view than I ever had before. Some of my old questions resurfaced. My experiences made things click into place.

Because I was working in schools, I met staff, teachers, administrators, as well as school guidance counselors. With their encouragement, I realized I should study counseling and resilience. I returned to the non-secure detention center with new eyes, but this time, instead of working in the residential side, I was hired into the school as a transition counselor. This gave me the other side of the many-sided coin. It allowed me to see how the kids performed in the classrooms, while talking with the teachers and crisis staff gave me even more insights into what kids were dealing with in school and in their homes.

I had been pretty insulated from poverty. I had no idea what poverty is. However, I became a “poverty tourist” one day when I volunteered as the supervisor of a teenager’s supervised visit home.

A supervised visit is something you do when the parent or the family isn’t trusted for some reason. I was to supervise a kid who stayed in a residential facility in lower Westchester County. The kids there had various mental health disorders and developmental disabilities. This experience there transformed my understanding of poverty, conditions I wouldn’t have appreciated or truly understood if I hadn’t actually walked into those conditions and ate in a home under those conditions.

Before this supervised visit, my life had been in danger–truly in danger–maybe two times. Once, when I decided to go clubbing with my friends in the real Bermuda outside of the resort area we were staying in; a second time when me and a friend broke up a fight in a college town in Westchester County where a kid pulled a gun; and this time, while walking up to an apartment building in the Bronx to supervise a client’s visit. My third time was when I was approached by a young man as I escorted the client into the courtyard of his building. If my client had not explained my presence, that I wasn’t a cop but that I was a friend, I have no doubt I might have been hurt. But at the time, I was amazed at the casual menace and the lack of build-up or drama. As before, with the other dangerous situations, I didn’t fully appreciate the danger I had been in. I was a tourist, which is a kind of spectator. And, I was young, so I had delusions of immortality to protect me.

The other thing was that it was surreal.

The building was surreal as well. I’d never seen anything like it. The door entering the building wasn’t locked. There was a huge hole in a wall of the lobby, rubble was on the floor. The hole was about four feet wide, and it had a big police tape across it like a diameter line in a geometry problem as if it would guard against intrusion. The lobby smelled like urine. We walked up a few flights of stairs. Something inside me awakened. This was this boy’s home, and I suddenly understood one reason he might have asked me to come. He trusted me. He trusted me not to disrespect him, not to insult him, or laugh or demean him. The awakened sense also told me that he was watching my reactions. Disgust, offense, indignation–any of those sentiments and emotions could reach my face and communicate more offenses than my words. So, I systematically dissolved my reactive mind, breathed through my nose, and turned off thinking. I compartmentalized certain aspects of my awareness. This was his home. It’s cool. Besides, it’s not like he’s going to stay here. He’s coming back to the cottages with me.

My client knocked on the door when we reached the stairs. When we were let in, we entered a small apartment with a sheet splitting a living room into makeshift bedrooms and a dining room into even smaller compartments. There was a bathroom and a bedroom. The kitchen was incredibly cramped as well. A woman was cooking with various pots covering the stove burners. She wore a housedress and it seemed that she barely fit between the stove and the countertop and the sink.

The kid introduced me to everyone, and I noticed there were small, black roaches running about. Some walked up and down the walls. My client asked me if I had ever had plantainos. I smiled and told him no. I figured this was a spanish dish or something, and I tried not to stare at the roaches and hoped again that I would not offend my client nor my hosts. The tv was tuned to some show in spanish. I had always thought the country he was from (left out for privacy) was from Africa. It wasn’t. Even though he was dark-skinned–he’s darker than me– and looked like he was african, but he was from a country in South America. I was a college graduate, but I knew nothing.

His mother spoke to me. She was asking me something. My client translated in his guttural, stuttering english, that his mother was asking me if I wanted to eat with them. The awakened inner voice took over. I couldn’t refuse food as a guest in someone’s home. Even with the roaches scuttling about and the close walls, the folding chair somebody opened up for me, and the dinner tray that someone set in front of me. She brought me a large plate with rice and beans, fried fish, shredded lettuce and tomato as a salad, and round, golden disks that reminded me of fried potatoes. I thanked her.

I smiled at everybody and sat in the folding chair. I pulled the tray closer, and pushed aside my worries about the fish, because I would eat it. I would eat everything on my plate. I picked up the fork. From this point, I only know that I was barely there. I was dead inside, numb, and I felt like somehow I was working my arms and hands and face from someplace deep inside. I looked about, watching everybody eat. My client brushed away a roach or two when they ran across his food. I did the same. And I ate. I mimicked his enthusiasm. My client asked me if I like the plantainos, the tostones. Those roundish, golden things on my plate. It crunched like french fries yet didn’t taste like potato. I tasted the salt on it. It would do. I brushed a roach from my tray, and I ate the fish and the rice and beans. I ate the salad that didn’t have salad dressing. I ate like he did, hungry and enthusiastic for his home-cooked meal that his mother made.

When we left, it was nearly night time. It was dusk. I stayed close to my client as we made our way out of the building into the courtyard. He gave some shadowy guys out there a “pound” as greeting and as a way of saying good bye. I nodded like I was “down”. My client said things like “he’s my friend” and “he’s cool”. We went out to the vehicle, and I made my way back to the residential center, glancing at the directions I had written down that would get us back to Westchester.

Memory Recall/Retrieval – Memory Processes – The Human Memory

StandardThe efficiency of memory recall can be increased to some extent by making inferences from our personal stockpile of world knowledge, and by our use of schema (plural: schemata). A schema is an organized mental structure or framework of pre-conceived ideas about the world and how it works, which we can use to make realistic inferences and assumptions about how to interpret and process information. Thus, our everyday communication consists not just of words and their meanings, but also of what is left out and mutually understood (e.g. if someone says “it is 3 o’clock”, our knowledge of the world usually allows us to know automatically whether it is 3am or 3pm). Such schemata are also applied to recalled memories, so that we can often flesh out details of a memory from just a skeleton memory of a central event or object. However, the use of schemata may also lead to memory errors as assumed or expected associated events are added that did not actually occur.

via Memory Recall/Retrieval – Memory Processes – The Human Memory.

via Memory Recall/Retrieval – Memory Processes – The Human Memory.

Science fairs aren’t actually preparing your kids to do anything

StandardTips and strategies for teaching the nature and process of science

Standardhttps://wonderlib.com/research-network/response/55818f0859526a550094d6a2

Could this be another reason why students do not pursue science? Because it’s taught like a history course or for English Language Arts, and it’s not taught honestly or accurately the way science is actually done by the professionals?

Tips and strategies for teaching the nature and process of science.

via Tips and strategies for teaching the nature and process of science.